While we grow up and develop our personalities we go through uncountable experiences that forge our character and make us who we are. Some of these experiences are beautiful, some of them are not. Problems at school, having trouble making friends or even a lack of self-esteem to name a few. It can be tough to cope with all of this. Some kids even have to deal with separated parents. Losing access to their parents has a profound impact on their development.

What Is the Problem?

Once grown up, some of us may realize that they suffer from minor or even mayor issues. In many cases they stem from memories that have never been properly digested. They have never been expressed and talked about. Like a bad seed that was planted in our minds and has grown over the years.

What if we prevented this seed from growing in the first place? Especially children struggle to talk about their problems. They often feel like they failed or that they did something wrong. When children feel put on the spot they will shut down.

Being in the middle of split parents is a tall order. Having a meaningful conversation about their feelings and concerns can be hard as they often have a loyalty conflict. The desire to make it right for both parents puts a huge pressure on them. Because they love both parents they are sometimes reluctant to talk about personal topics and feelings as they don't want to make either parent sad or be the source of a conflict. It is difficult for them to express their opinion if that meant they would have to take sides. They are afraid of being judged.

How does Animo solve this?

As mentioned before, when children feel put on the spot, this have a very hard time to talk about their feelings. Animo gamifies the facilitation of that communication. It's the game which asks the questions, not the parent or care taker. Children accept this as part of the game logic and as a result feel less judged. Topics may come up which can be concerning. Animo doesn't solve these problems, but it gives you a tool to find out about them. Because how can you solve a problem that you don't know about?

Concept

Animo is an interactive board game for children that facilitates conversations between them and their parents or other care takers. It provides the children with a confined and safe space that makes it easier to reflect on and talk about feelings and difficult topics. It does that without giving them the feeling of being judged. It allows them to express themselves in a playful way.

It is a shared experience for families and school kids to make communicating their fears, their concerns but also their joy more seamless. It's a communication tool that lets the players get to know each other better on an emotional level.

Animo is to be played by the children and their parent(s) or other caretakers.

Relevance

As of 2017, in Denmark nearly half of all marriages fail, despite the country's reputation as the happiest in the EU. Every fifth home with children has just one parent.

At Maglegårdsskolen which was a collaborator for this project, 200 out of 700 children live in divorced families. They take it as a serious topic and facilitate sessions for the affected children where they are given the opportunity to talk about their feelings. nfortunately at home these children usually don't talk much about what's on their minds.

Target Audience

Animo was initially specifically designed for children of split families to provide specific value to this target audience. Over the various iterations of the project I open it up so that it works for all children. This in turn leads to a de-stigmatization of the children of split families. Giving these children a platform to talk about difficult topics together allows them to blend better with the other kids.

In the current versio mainly issues in regard to the faily situation and issues at school/kindergarten are covered by Animo. Further card sets could specifically address topics such as a loss of a family member or a pet, an upcoming divorce or moving to another place.

As the covered topics are sensitive topics, Animo requires considerate use by the parents and care takers.

How it works

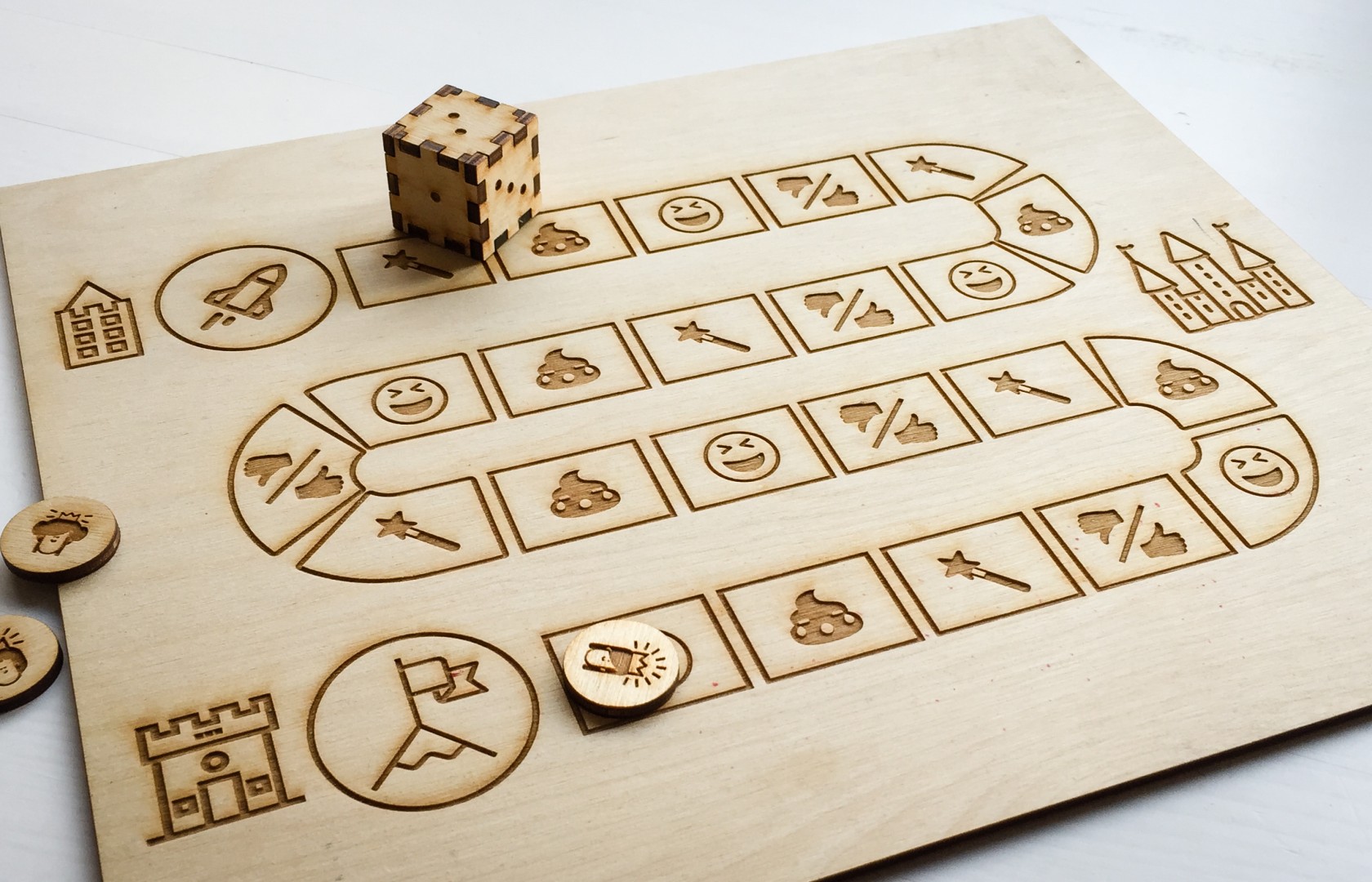

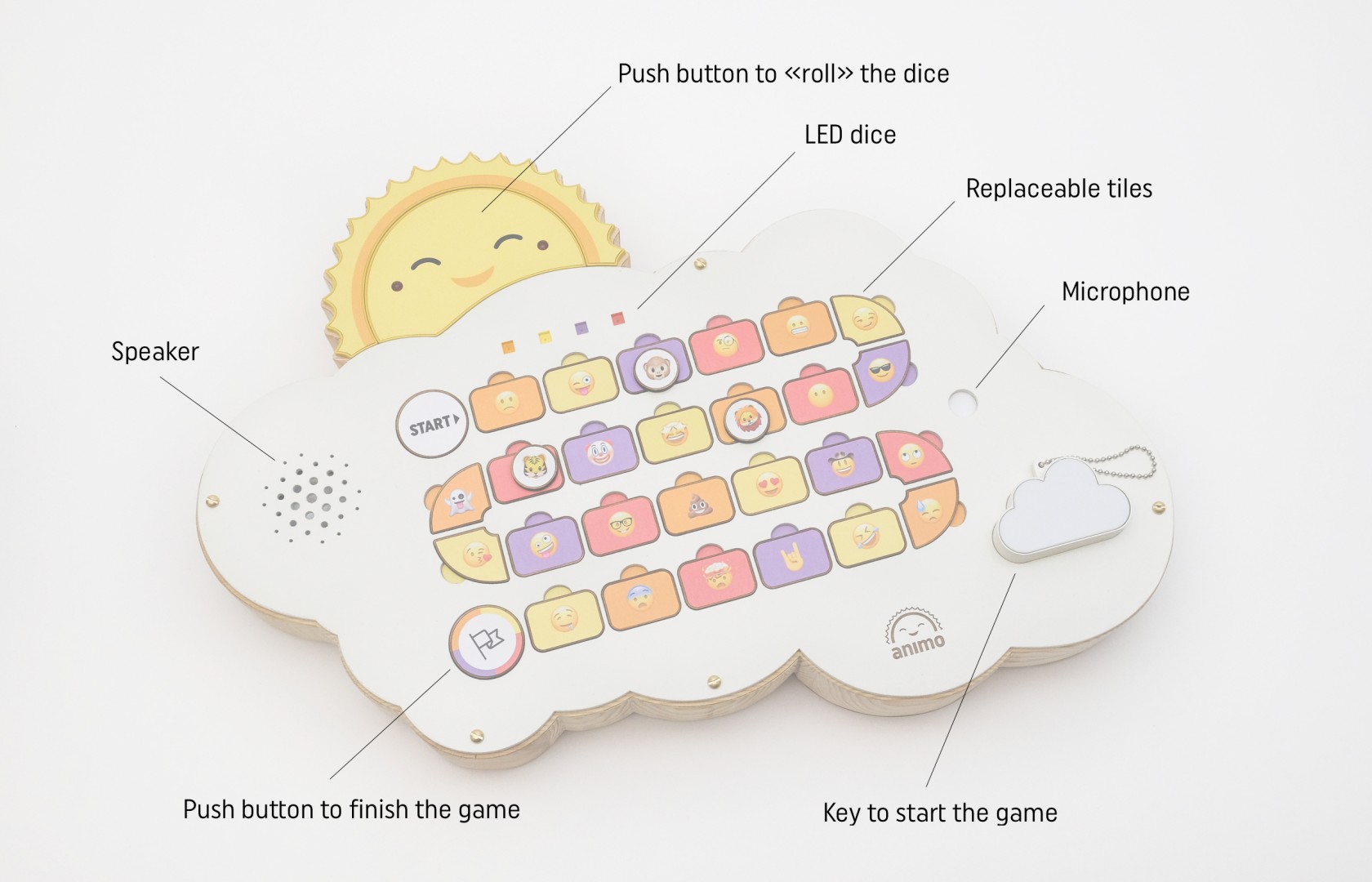

The players set up the game together by placing the tiles on the fields with the matching color on the board. This smoothens the game start as this llows them to gt into game mode before the actual game starts. One child is chosen to start the game. They do so by placing the cloud token onto the placeholder.

Each player chooses an avatar token that they use to move along the fields on the board. When it's their turn, the player «rolls» a digital dice. The player then moves its avatar to the next field that has the indicated color. The player drws a card with a the matching color. The categories are as follows:

- Delight: Talk about a positive topic. (e.g. What was the most beautiful moment today?)

- Concern: Talk about a negative topic. (e.g. When was the last time someone was mean to you?)

- Thought: Draw a situation, people etc. (e.g. Draw a picture of you and your best friend.)

- Action: A fun activity that balances out the seriousness of the game. (e.g. Take a small object and balance it on your nose.)

During my research I realized that children's true wishes often don't align with what the parents think they are. Therefore a special 'Wish' card allows the children to freely express a wish for something to do together. If the children land on the wish field during the game they shall get their wish fulfilled.

While the players talk about positive or negative topics the board game records what they say so it can be played back later.

As the players complete the given tasks they collect cloud tokens. For yellow and purple cards they receive one token, for orange and red cards the get two tokens.

Once a player reaches the goal, the game ends. The player pushes the goal button which starts the playback of what was recorded on the yellow fields. This allows the player to hear the positive things again and leave the game with a positive mind. The player who collected the most tokens wins the game.

Reflection For Parents

When the children have gone to bed the parents can get back to the board game and listen to the concerning things that were said during the game. To invoke this hidden playback function they do a long press on the «goal» button.

As they listen to the recordings they can go through the reflection cards which help them to guide their reflection process. On these cards are simple prompts such as, «My children and I, we should do more of…» or «My children and I, we should do less of…». These prompts aim to help the parent to think about what they could do to make a positive change in their children's lives. They can write down their thoughts in the Animo companion app which helps them to keep track of their children's emotional state.

The Recording Function

For the children, the recording function serves as a way of ending the game with a positive feeling. For parents, it's a way to reflect on the positive and negative things that were said during the game. For class teachers it's a bit different. Imagine you are the class teacher and while playing the game you hear the children talking about bullying or physical violence. How would you react? In that case you may use the recordings to let an expert analyse them and make a decision together about what to do.

Project Details

The brief that I set for myself was to have a look at how separated parents who bring up their children together interact with each other to give the child a seamless experience and a feeling of being at home. Based on my own observations there can be issues around reliability, trust, safety and consensus when it comes to co-parenting. Raising a child in a consistent way can be difficult if the parents live apart and have different ideas of parenting and living. Often children are in the center of conflicts between the parents. I believe the safety and wellbeing of the child should have the highest priority.

Everybody involved in this situation has their own needs. Through research, I investigated how to use design thinking to come up with a solution that supports both parents and children.

How might we allow children of split families to talk about difficult topics and express their feelings in a playful way?

Read moreInitial Explorations

Children of split families can be facing different kind of challenges that stem from being between their parents.

Over four different prototypes I iterated on new ways to deal with these challenges.

One of the problems is that the back and forth between the two homes and potentially the daycare combined with the lack of understanding of time confuses the children and compromise their feeling of continuity.

When they are at daycare they sometimes don't know who's gonna pick them up. When they wake up at night they sometimes don't know where they are.

Could a physical installation help them to understand their agenda and therefore make the transition between their homes more seamless? With a first prototype I explored ways to give the children a better understanding of their schedule. I used a projection and physical tokens which should help the children better understand their week plan and provide them with an understanding what happens next and who's gonna take care of them.

Even though the interaction with the physical tokens worked well, the concept was too complicated and too abstract for young children to understand. As a result the prototype didn't have the desired effect.

Another issue is that separated parents miss out on a lot of moments that are important for the children to gain self confidence when they're not with them. They don't get the chance to witness and celebrate these moments with them. The parents don't send each other pictures so often and they usually don't have a shared photo album. Can pictures and videos be used as a medium to celebrate important moments with the parent who wasn’t there? With a second prototype I designed a service and implemented a working app that allows to celebrate the children's best moments and achievements together and reward the child for taking a step forward.

The app allows to take short videos of the children's important moments. A static image is created from the video and uploaded to the service. The service prints a physical sticker and an image and sends it to the child's parents. Mounting the sticker to the image allows the moment to come alive and celebrate it together as they hover their smart phone over the image.

This concept was well received by both parents and their children but at the same time it reminded the children that one of the parents misses out on more moments than the other one.

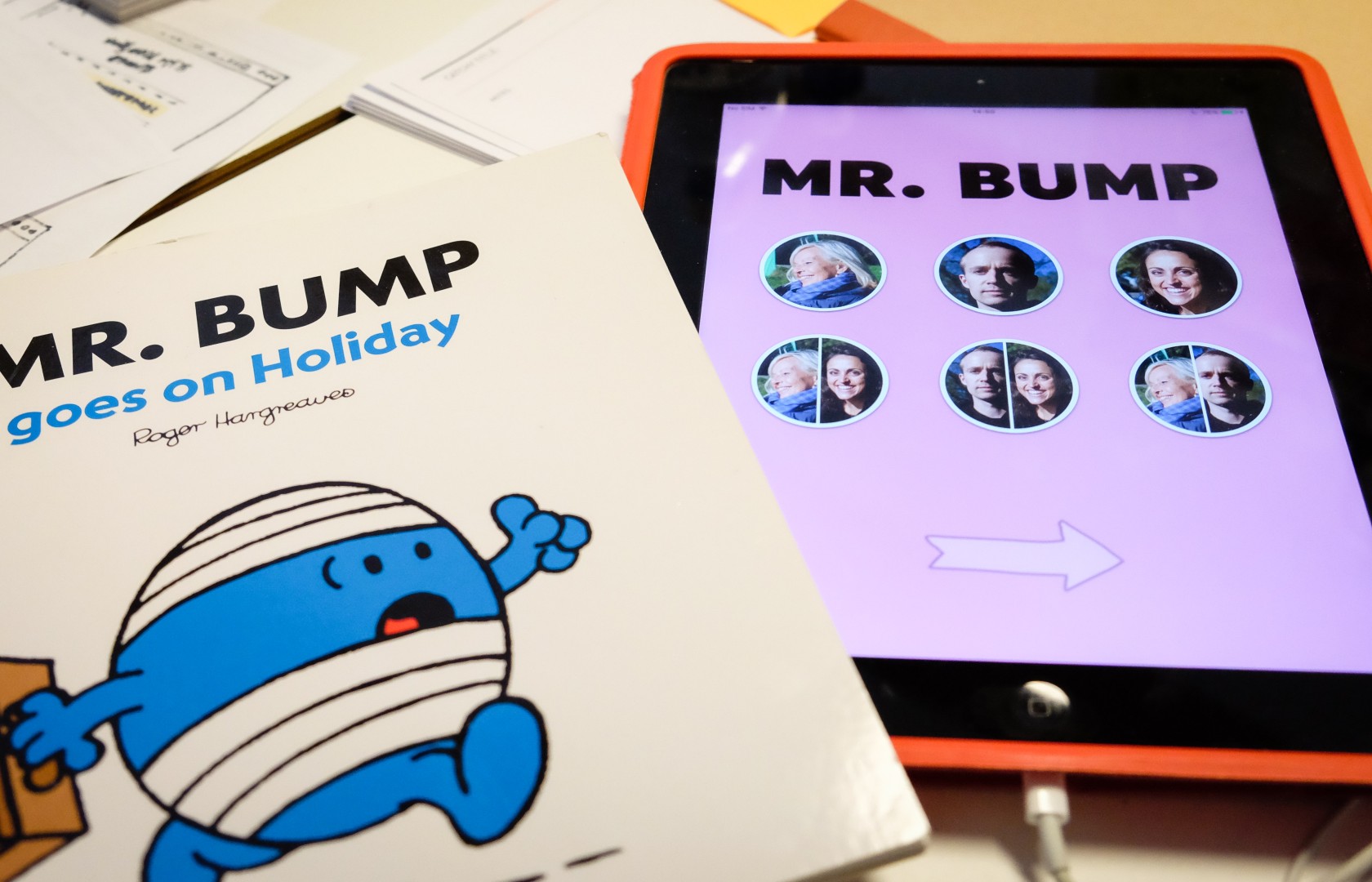

Another problem is that children of separated parents are mostly disconnected from one parent when they are staying with the other one. The parents decide when the child stays and with whom they can spend time. Would a storytelling platform make them feel more connected to the absent family members if the children can decide who reads a story with them? With the third prototype I designed a system that connects the child with the family members over stories. The child gets to decide who should be part of the storytelling time.

The family members record short parts of a story using an app. By arranging and assigning the narraters in different ways the children can then listen to different versions of that story on a digital or physical interface.

This concept has a lot of potential as the prototype seemed to have the desired effect of connecting them with remote family members. However, in some cases it causes the children to miss the absent family members even more.

The biggest issue that I found with split families is communication or the lack thereof. Not only between the parents but also between the children and the parents. Would they feel more comfortable to talk about feelings if it’s through a game? As a fourth prototype I designed a board game that should help the parents to find out what's on their children's mind. As this concept seemed to tackle a core problem of split families I decided to go forward with that one.

Iteration

I saw the potential in a board game for separated parents and their children to serve as a conversation platform. When they play the game with the child it allows everyone to express themselves through a game character and learn about each other's needs and wishes. One of the psychologists who I collaborated with, Dr. Elisabeth Maaß, said «The inner needs of children at this age are mainly expressed through play.». This gave me confidence that I was going in the right direction with a board game. As a design criterion I defined the product to be a non-digital solution. From what I observed, this seemed to be a good choice as a physical board game affords invention of new rules and mini games with the existing game components. The children are limited only by their own imaginations and creativity. In addition to that, holding something in their hands while they were thinking and playing had a calming effect on them.

The first version of the board game was divided in two sections each being about one of their homes. Different types of fields would among other things prompt them to tell about something they wish or about something they like/dislike about their home and the corresponding parent.

An early test with a 4.5 years old revealed that it was apparently fun to play despite the therapeutical character. Interesting things came up especially when talking about things that the child didn't like about each parent.

For the next iteration of the game I worked on the form factor and re-designed the game logic to be more diversified. I ran co-creation sessions with the children to help me figure this out.

Since I had found a form factor that was very well received by the children who I tested the game with, I decided to mainly focus on the game contents and the game interaction for the following iterations.

Designing the User Experience

There are a couple of important questions that came up after running the first few test sessions:

- What kind of prompts and questions can open up the right conversations?

- How can we allow the parents to reflect on the topics that come up during the game?

- How can we allow the child to leave the game with a positive thought even though they potentially talked about negative topics?

- How do we make the child stay connected with the game?

- How can we keep the game engaging over time?

- How can we make the game a competition without compromising its functionality as a communication tool?

- How does it affect the game if more than one parent and more than one child participates?

Is the game duration right?

Answers to the above questions had to be found by iterating on the game logic, the game contents and the components.

Answers to the above questions had to be found by iterating on the game logic, the game contents and the components.

Testing and Refining the User Experience

The game should remain interesting over time and physically appeal to different tastes. I realized that after the first test, when the children started to ask me if there was also a dinosaur or a Minions version. Therefore I co-created with children to come up with different themes so that the tiles can be replaced and to give it some sort of collector's value.

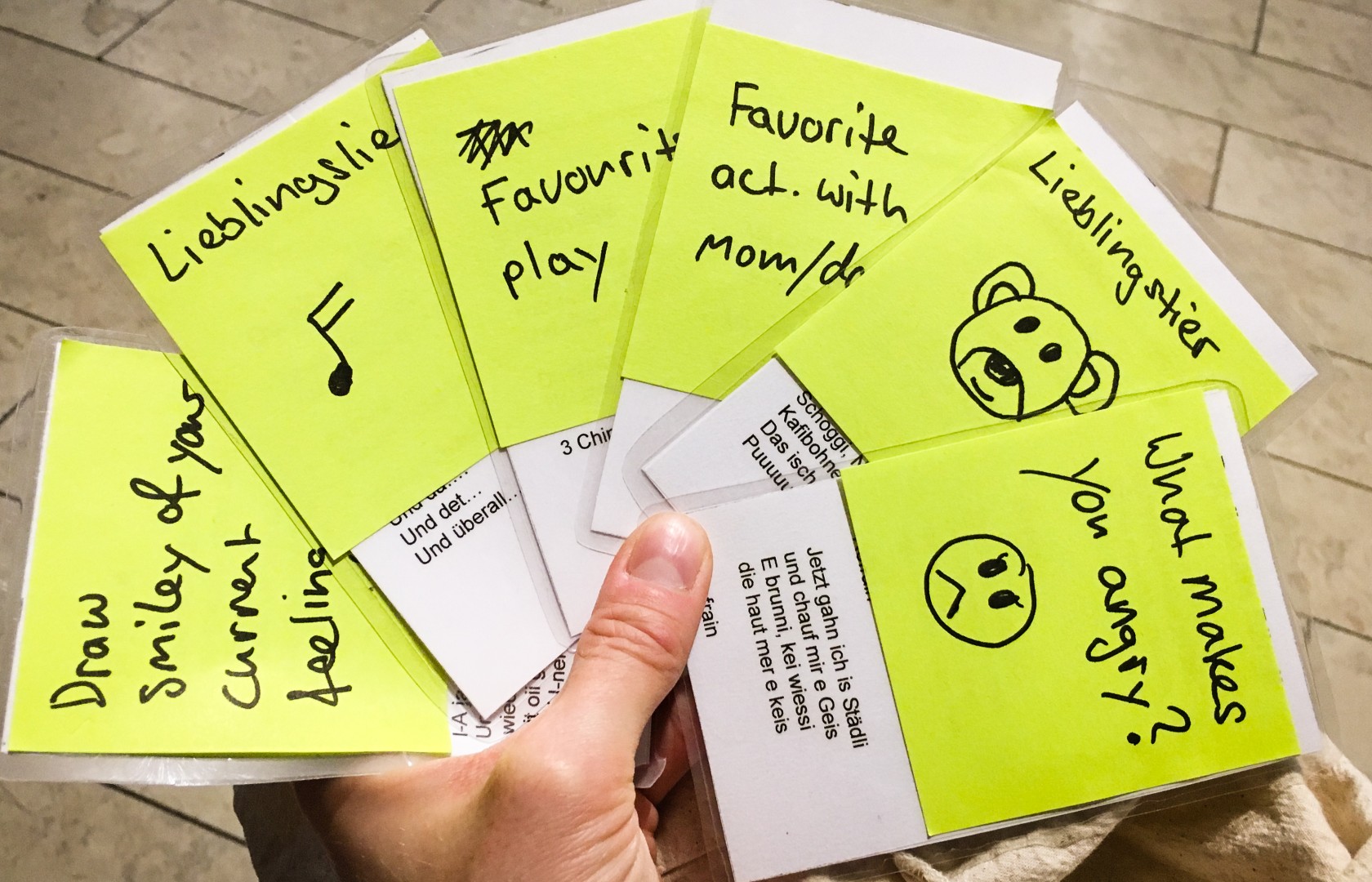

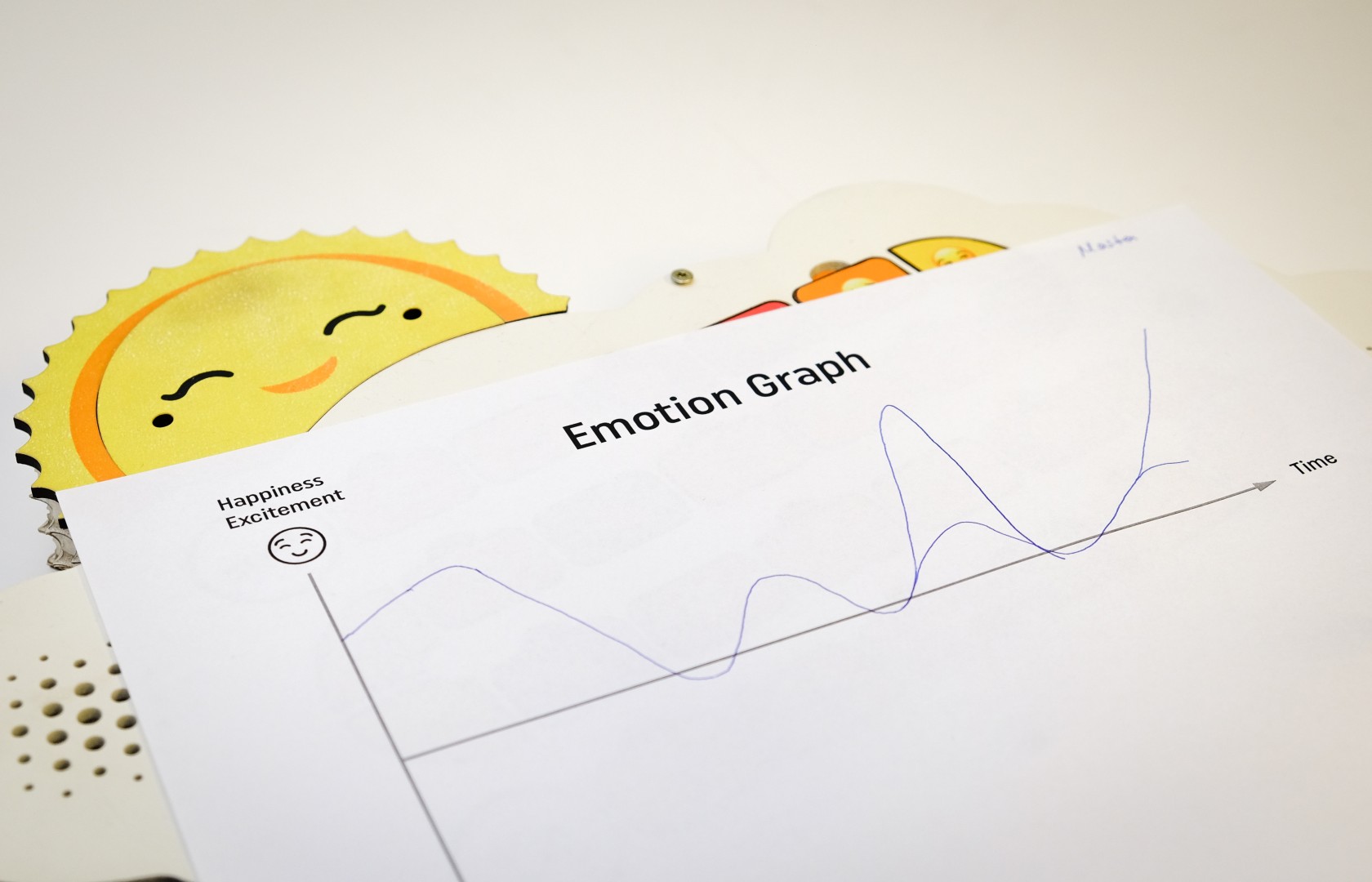

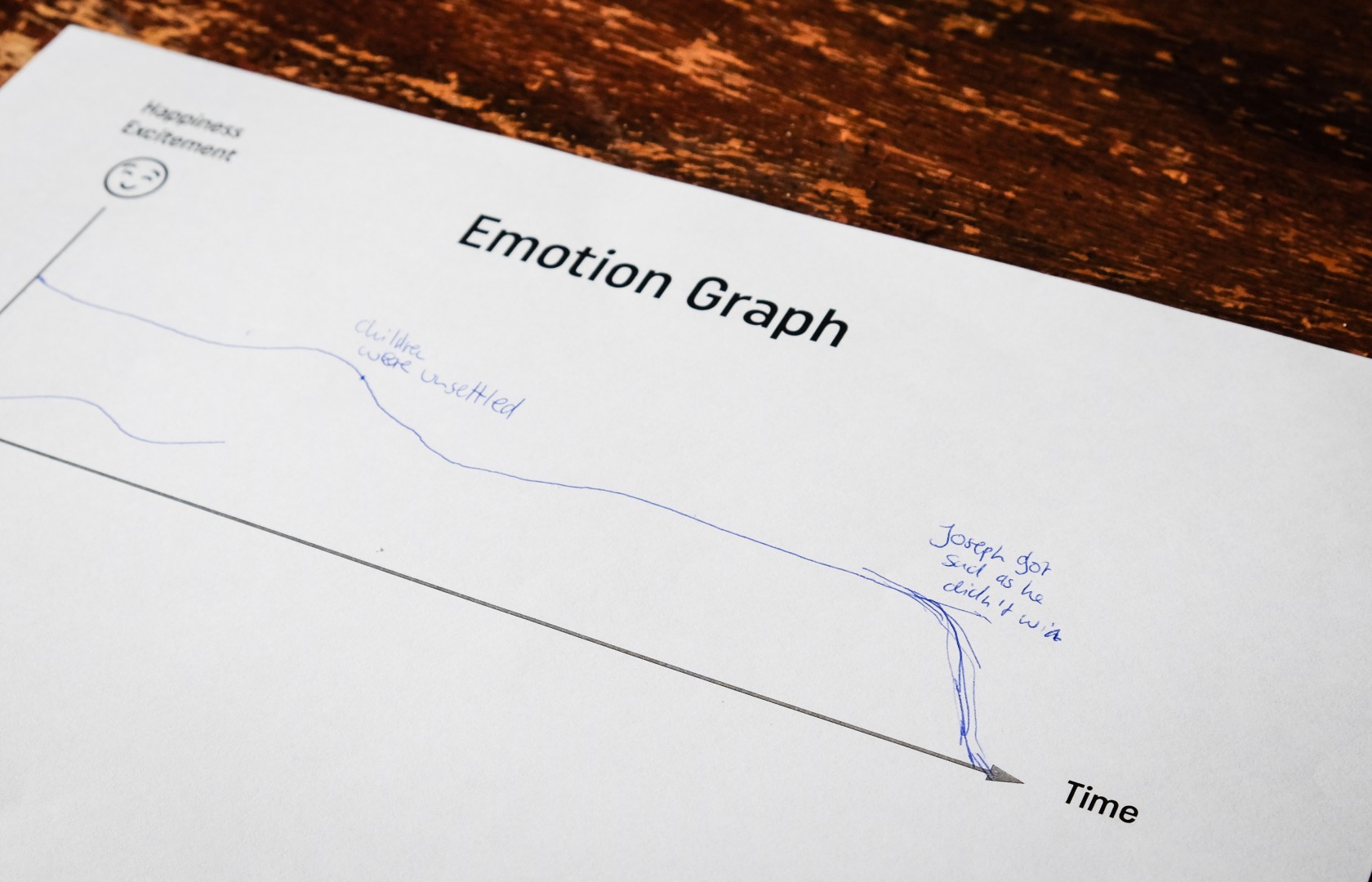

As for the game contents it's crucial to establish a set of prompts and questions that balance out fun and communication. The communicational questions should hit the sweet spot where the children have to reflect on their feelings but still feel comfortable to talk. Sometimes topics come up that may make the parent feel uneasy. These are exactly the difficult topics that the parents need to talk about with their children. I let the players draw an emotional graph to see and discuss how they felt while playing the game. I used their emotional response to modify and create new prompts for the game.

Sabine Brunner who is the other psychologist I worked with said that «It's also important to include the children's view about their parents.». As a result I included questions that make the parents understand how the children see their parents.

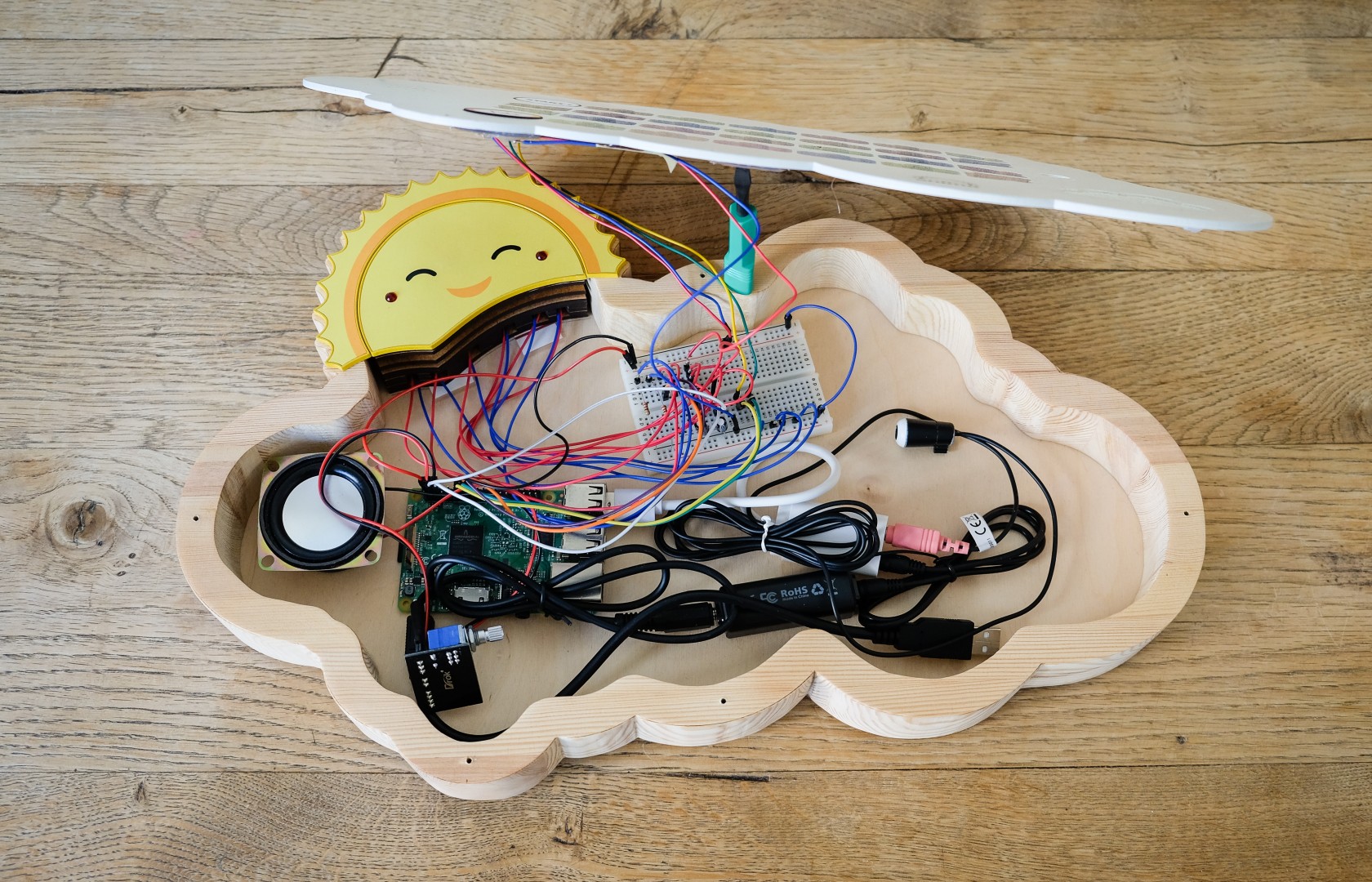

Based on the experience of the first testing sessions I realized that a game session can take up to two hours, which is good. However it can be difficult for the parents to remember everything that was said during the game. Therefore I decided to include a recording function. By replacing the cubic dice with a digital one, the game always knows what field the current player is on and can record if it's a relevant communicational field.

In the next iteration I designed reflection cards to guide the parents' reflection when they are listening to the audio recording of the game session.

After noticing that some of the children left the game a bit daunted when they were talking about negative feelings and emotions before the game ended, I decided to give the recording functionality another purpose. I made use of it to allow the child to leave the game with a positive feeling instead. When the first player reaches the goal, the game ends and that player pushes the goal button. This starts a playback of the things that were recorded while the players were on fields with questions about positive topics. Hearing these positive words again as the game ends should remind the children of them and should get them back to a positive emotional state if needed.

In some test sessions it became clear that the game logic had an existential flaw. Because the children would win the game by getting to the goal first, they were discouraged if could see that they've fallen behind. As a result they would cease to engage in the game.

I reached out to a game designer to help me find a solution. We came up with the idea of winning the game by collecting tokens. Collecting objects throughout the game allows for a more subtle competition.

This completely flipped the game logic. Kids now wanted to get to the goal as slowly as possible so they can collect more tokens which leads to more conversations.

In the following iteration of Animo I included a scoring scheme. The more difficult fields get them two tokens instead of one which encourages them to express themselves more deeply about the given topic.

The idea is that Animo is played repeatedly every couple of weeks. In order for this to work, the children need to be motivated to do so. During the research phase I heard and witnessed many times that to make children connected to an object you have to let them take ownership over it. Thus for Animo I designed a personal token that allows the child to start and unlock the game. They can keep the token with them and use it as a night light or keychain if they wish.

Process

Animo was carried out over ten weeks. During 14 interviews with parents who live together, separated parents, grown ups with divorced parents, split family children and day care givers I conducted insights that allowed me to uncover the problems and needs of these people. After defining a design challenge I ran brainstorming sessions with my peers to explore the problem space. Co-creation sessions with children and their parents helped me to narrow down possible design solution which I then prototyped. After prototyping different solutions I decided to pursue the board game. After another 7 iterations of prototyping and testing with 20 different children, 5 families and 3 schools, I ended up with the current version of Animo.

Technology

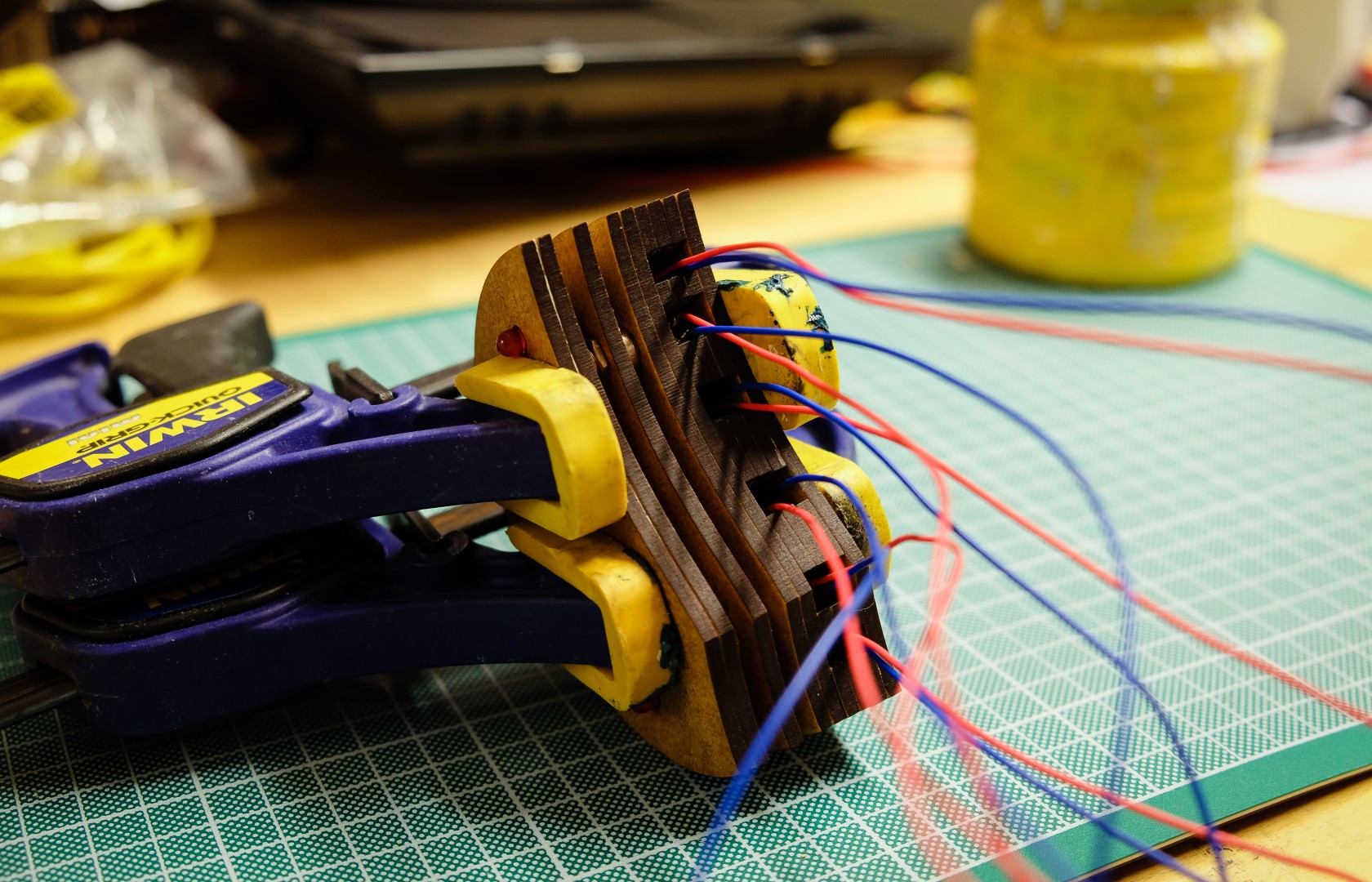

Animo is powered by a Raspberry Pi 3, audio components, buttons and LEDs. A Python application controls the LEDs and reads the button states. It records speech whenever the LED dice lights up in orange or yellow and cuts off the silent parts.

Impact

When I tested Animo with a whole school class I got an understanding of the classroom dynamics. Some children mentioned that one of their class mates is mean to them. Playing the game with that child unexpectedly revealed that it was this child’s way of showing their discomfort about their feeling of not being accepted in the class. The teacher assistant was surprised about the issues that were uncovered through playing the game.

Following our collaboration, the Maglegårdsskolen in Copenhagen asked me to produce the board game for them because they would like to add it to their toolset for the sessions they run every week.

The International School of Hellerup, Copenhagen which was another collaborating school asked me to hold a lecture about board game design for their design class. The lecture and workshop was held on December 14th 2017 for around 40 students (age 10–11).

One of the split family respondents sent me the following feedback:

«I'd like to shortly add that my son was a bit tired and pensive on the days that followed playing your game and also that he has since then become even more confident in telling me and my Ex how he feels about things. And, that he's assertiveness has been making us more aware and respectful of his needs. So 👍!»

Having made a small positivie impact on a family's life was the best possible reward I could get as a designer.

Contribution

As this this was individual work for my graduation project, all research, concepts, prototypes and testing were done by me.

Links: Why Are Physical Educational Toys Better for Young Children | Denmark's divorce express | More single parents in Denmark than ever before